My friend gave me a talisman. It’s a silver ring, the band and the ornament molded to look like twigs. The ornament is the rune tiwaz, the Proto-Germanic precursor to the English letter T. It resembles an upward-pointing arrow. Long ago the shape was understood to represent a spear.

The Old Norse called the rune Týr, named for the one-handed god of war and the law. In the Poetic Edda, the Valkyrie Sigrdrífa instructs the hero Sigurd in the rune’s magical use:

Carve them

into your sword's hilt, on the blade guards

and the blades, invoking Týr’s name twice.

Such an invocation has been found carved into amulets, 1500 years old or more—stacks of centipede-like tiwaz runes all pointing upward. Whether the makers or the wearers were following the Valkyrie’s instruction, no one can say, but people who still care about such things call it the victory rune, as Sigrdrífa does.

My ring shows the tiwaz doubled and opposed, not stacked as on the old amulets. The two spears point opposite directions and share a shaft. My friend gave it to me in my second year of law school. She told me she’d imagined it as a courtroom talisman—the double-invocation of Týr’s rune for victory, balanced like the scales of justice.

I don’t believe in Týr’s power to help or harm my case. I don’t believe in Týr. Yet I’m selective about when I invoke him. To carve the victory rune into a sword hilt was to try to tip the scales in your favor, such that your blade ended up in someone else’s guts rather than someone else’s blade in yours at a pivotal blade-related moment. It feels like stolen valor somehow, doesn’t it, to equate a stuffy motion hearing with tribal warfare in 3rd-century Scandinavia.

But then again: The Edda tells us that Týr lost his hand because he freely laid it between the jaws of the giant wolf Fenris, knowing that its loss would permit Fenris’ magical binding and forestall the end of the world. He understood that he couldn’t defeat the wolf in straightforward combat, and that if he failed to bind the monster in the first attempt, it would never be bound.

I think, if Týr Law-Giver existed, if he could care about such things, he would understand that there’s more than one kind of battle, more than one way to measure victory.

And so I don’t wear the ring to every hearing, but I wear it when it feels right to do so. Whatever that means. When I do, I wear it on the first finger of my left hand, never another. I take it off when I get home. I polish it when it tarnishes.

A few years ago, I looked around and realized that I was becoming one of the only women I knew who didn’t publicly identify as a witch. Suddenly everybody’s social media was all altar cloths and quartz points and sage bundles and tarot spreads. Suddenly I was getting invited to homemade Imbolc festivals and Facebook-invited to ritual dance parties at a local club.

Now it’s everywhere. Every small-town clothing boutique will sell you crystals these days. There’s a vending machine in a brewpub here from which you can buy a rune reading, or a pair of healing glasses color-coded to one of your chakras. You can buy t-shirts and custom enamel pins with witchy trappings, or spring for framed wall art from Marshall’s that says WITCHY VIBES in spidery font on a background of purple sparkles.

When I was a kid, girls went to the mall and bought books about solitary Wicca by authors with names like Silver RavenWolf and Starhawk. And then we went online, where forums full of people older than us explained the shortcomings of our books. You couldn’t expect to practice Wicca without a coven, they told us. You couldn’t expect to initiate yourself. You couldn’t expect to worship a sweet, safe, flower-garlanded Goddess unless you reckoned with her consort, hornéd Cernunnos. You couldn’t divorce pagan ritual from sex, from money, from fame, from the desire to lay your enemies low. On the pagan Internet Silver RavenWolf was referred to only by her initials, and to invoke her name in earnest branded you an infant, a poseur, a trend-chaser, closed out of the ranks of serious practitioners.

Serious practitioners, to be clear, of magic. People who went into the woods when the position of the moon was most auspicious, often in groups, sometimes naked, and called on the names of beings in whose literal existence they firmly believed. They asked gods and spirits to possess their bodies. The smoke from their altars, they said, wafted upward to real nostrils, and in exchange for the smoke they were given power to make money, to win love, to heal their illnesses, to destroy their enemies. They read stars and arranged stones, they fasted and traveled, to bring the physical world into such alignment that a bridge would open between their minds and the gods as they slept and bring prophetic dreams.

Some of them believed they had the souls of animals and could walk ethereal realms in other bodies. Some of them really, truly believed in fairies. Many of them wouldn’t talk to you if you didn’t have a certain baseline of kabbalistic knowledge. They were aloof, sanctimonious, attention-seeking. They described with shrouded self-importance their exhaustion in the days after a ritual, the agony and ecstasy of working with their chosen deities.

I tried for a while to believe in it as a kid, but it didn’t pan out.

I never even attempted the kind of magic my forum friends said they did. I was raised a Catholic—I knew that gods were jealous. If I was going to use the power of the gods, I thought, I couldn’t make the ritual a test of their existence. I had to believe first.

And so I tried to believe. I tried so hard I even managed to manufacture real reverence once or twice, to get so lost in my daydreams that I could imagine, briefly, that one of them had been planted in me from outside. But it never lasted. I never felt ready for initiation. I always knew I was just telling myself a story.

Witchcraft, in the form it surrounds me, isn’t a religion. It’s a big, sprawling, fuzzy-edged vibe, all woodland creatures and flower symbology and draped shawls and crystal necklaces and sage bundles and star signs and bespoke scents. It’s about setting intentions and manifesting positivity and calling in energy.

Always energy—never gods. Witchcraft is atheistic now. Everybody assures me of this when I ask about their practices. In fact, everybody assures me that they don’t believe in any of it. Not the tarot, not the crystals, not the rituals. The altar smoke rises to no one. That’s the point.

They’re telling themselves a story, they tell me. The story is the magic, and the way the story makes you feel. It is an intellectual and a social exercise. It’s an excuse to own beautiful and comforting things and imbue them with profound personal meaning. It reveres creativity; it casts traditionally feminine pursuits in a more feminist light. The Wheel of the Year gives shape to nine-to-five days grown ever more detached from the daylight hours, a capitalistic life lived through a screen. Learning to recognize the animals and herbs and flowers and trees that mark the passage of the seasons wrests some sense of peace and predictability from life in a big city. Knowing the catalog of symbols, what the cards and stones and flowers represent, feels like being an expert in a subject no one will ever test you on.

I understand this. But I can’t do it. I’ve spent long enough standing in front of an altar seeking something greater than myself and finding only myself.

I am such a dull thing, such a derivative thing. There’s no world in which I could mistake the thoughts in my own head for a god’s thoughts.

My friend gave me a talisman. It’s a piece of polished rose quartz, of a size to fit in the palm of the hand. The weight is satisfying. There is a crevice in it that the tumbler didn’t quite smooth out, inviting the motion of a thumb over it.

She gave it to us as a wedding gift. The gift itself was less the stone than the time she spent preparing the stone to be a gift.

She chose it from among many similar-sized polished stones. She placed it on an altar to be cleansed. She meditated with it. She asked that it be imbued with the energy of Aphrodite, for love and passion. I know, vaguely, some of the things that people do with crystals, and maybe she did some of those, too—maybe she left it overnight in a bowl of salt, to purify it. Maybe she dropped it in water and let it rest under a moonbeam when the moon was in proper phase, to fill it with power. I don’t think she believes in Aphrodite, but the idea of Aphrodite suffices. A stone with an idea in it has power, too.

In our house it lives on the windowsill, surrounded by our houseplants. I don’t remember if she gave us the tiny box it peeks out of, or if we found that and brought the two together, but that’s its place now. Having it there has taken on the force of tradition. It would be unacceptably arbitrary to move it from the place we arbitrarily placed it.

Witchcraft is one of those things, like many other things now, that carries with it a subversive aesthetic despite being wildly popular. It wears the trappings of a leftist counterculture even though words like manifest and energy now get thrown around in board meetings. It seems to go without saying—without explanation—that it’s kind of anti-capitalist.

Over time, the woodsy pagan vibe and the bright-eyed Instagram-reiki-healer vibe have bled into each other. An affirmative, pastel-colored spirituality pervades the way people—women—talk to each other, doused in a self-effacing deniability. Nobody will cop to actually believing that Mercury in retrograde means anything, but everybody sure as hell knows when Mercury is in retrograde.

It’s all so noncommittal when you scroll through a thousand pages of it, so blandly, vaguely positive. It clings relentlessly to that which is both unverifiable and unobjectionable. The vibe is held together by a loose aesthetic, yet the practice is individualistic to the point of total meaninglessness, because to define anything as strictly as a belief would be exclusionary somehow.

I can’t get my hands around it. It slides away. You can talk astrology for half a straight hour with a group of people who will all retreat from the point like woodlice under a flashlight the instant it is suggested they might take it seriously. They don’t need anyone else to mock them for it – something inside them is already mocking them. And yet we’ll talk astrology for half a straight hour before someone flinches.

It leaves me grasping at vapor. Why are we all talking in code? Why are we using the language of mysticism, of belief, to talk exclusively about things we don’t believe?

At this point I wish a god would appear to somebody, somewhere. I wish somebody I know would tell me they had a prophetic dream. Something inexorable, something fixed. Something you can get your teeth into.

My friend gave me a talisman. She brought them in a stack to a bachelorette party. She pulled them from her skirt pocket on the morning side of midnight, little rectangles of tight-weave aida fabric with sigils embroidered into them in dark blue thread.

I was drunk and joyful, wearing my jacket zipped up over my bra because I’d upended a glass of wine onto the shirt I’d arrived in. Several glasses of punch ago I’d lit a green candle at the hostess’s invitation, setting my intentions for prosperity for the couple. I’d almost cried with love at the sight of the silver Goodwill dish all covered in candles, covered in wishes: Green for prosperity, pink for passion, white for healing, black for strength, blue for communication.

“I just brought these,” my friend said, rifling through them as I leaned over to look. “I thought people could take one if they wanted.”

I was a week into the busiest season of my year, and my buzz was the kind of buzz you can only get when you’ve got a real source of stress to avoid. “Do you have one for working in the legislature?” I asked.

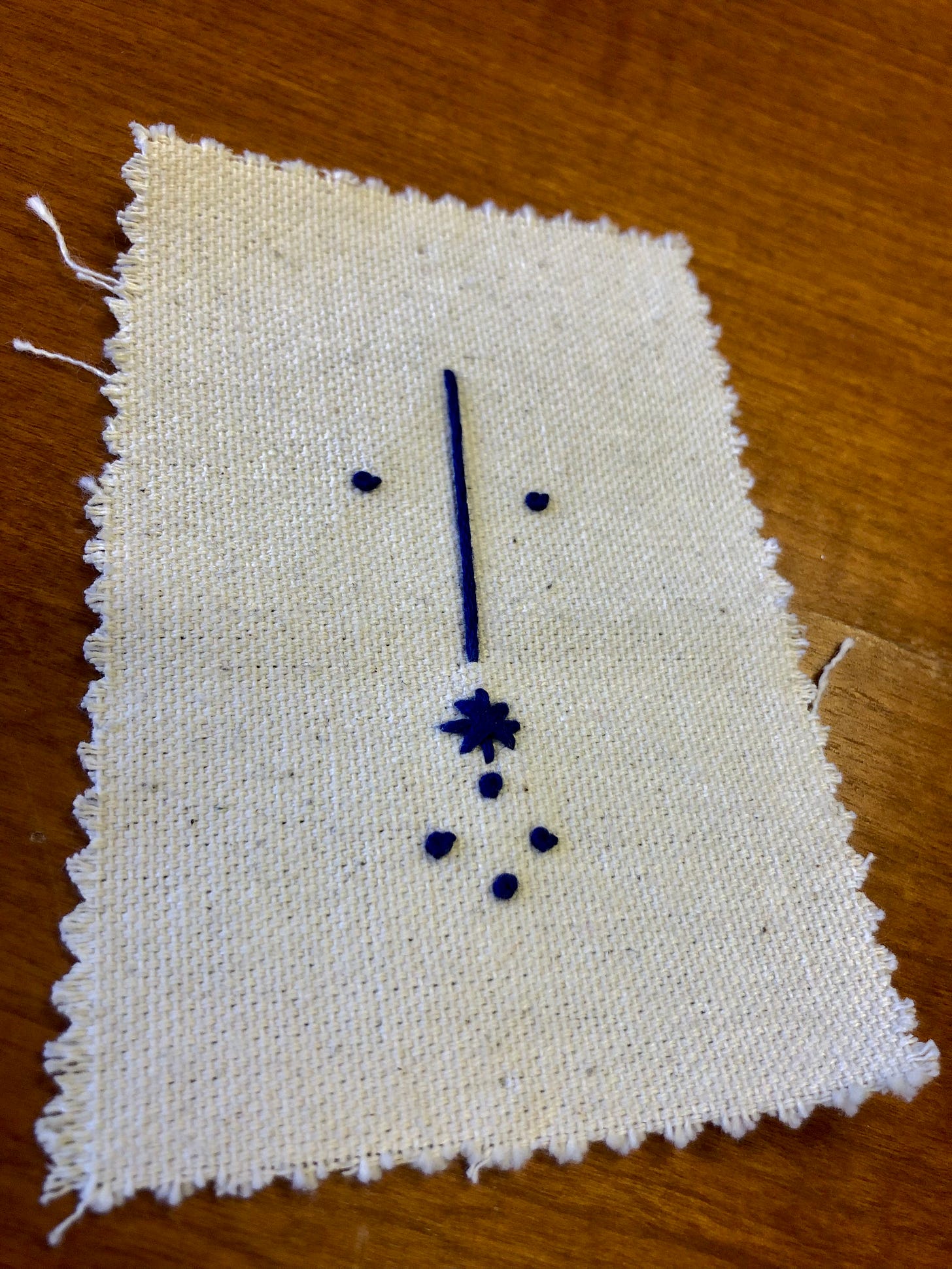

She frowned, narrowed her eyes at the stack, and said, “Yes.” She handed me a sigil that looked like a dandelion, or a sparkler; one straight line crowned with a star and four dots, flanked by a dot on either side.

My friend designs sigils based in astronomy, botany, and chemistry and stitches them herself. The sigil she gave me is based on a steel molecule. She told me it means resilience.

The Monday after the party, I took it to work and pinned it to the wall beside my monitor with white thumbtacks. I tucked it into my pocket on my way out the door to the legislative campus. I carried it with me into the Senate chamber.

I don’t even know what I would ask the gods for, if I believed in them.

You have to think pretty highly of yourself to think a god would stoop to work beside you, don’t you? To see them as colleagues and not superiors. I don’t have any projects a god would be interested in. I’m too fortunate: I don’t have any enemies to lay low; I don’t need to win love; I don’t need to burn a candle for wealth.

In ancient times, when people prayed to Odin, they prayed that he would look away from them. O capricious lord, Odin Deceiver, when you walk the battlefield choose my enemy for death and look not upon me. Let me be beneath your notice.

There’s a draw, not to believing in the gods, but to being the kind of person who would believe in the gods. I am never going to stand wild-eyed on any moor or send my spirit to inhabit a wolf’s body in my dreams. I am never going to have problems a pagan god could solve.

There’s the temptation in a noncommittal witchcraft: To believe with a little too much effort that I could be the wild-eyed moor-dweller. To learn to be satisfied with the shadow of real reverence. To stop just short of making the God I grew up with jealous.

When I was in college I bought my first tarot deck. It’s a secondhand copy of Clive Barrett’s The Norse Tarot. Týr appears in it as XI Strength, locked in struggle with the half-bound Fenris, one hand tight on the magic rope and the other, still attached to his wrist, in the wolf’s mouth.

The card on which it’s based, illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith in around 1909, depicts a woman in a white robe and flower garland bending over an open-mouthed lion, her hands resting gently on either side of its head. Her expression is serene. The lion gazes up at her in something between fear and adoration, tail tucked meekly between its legs.

Strength, turned over in a reading, represents power gained through negotiation, fortitude, and an understanding of one’s opponent. Strength wins by nonviolent negation of the threat. Strength understands that there is more than one kind of battle, and more than one way to measure victory.

Nowadays, our household collection of tarot decks lives in a pretty wood cabinet with a glass door. We take them out when friends are over; we lie sprawled on the couch, on the floor, drinking wine and handing cards back and forth. We pick which deck to read from based on the season, on the phase of the moon, on the question asked. This deck is gentle. This deck is solemn. This deck tells it like it is. Here—this one makes me think of you.

My friend gave me a talisman. My friend turned over the Ten of Cups. I ask the gods for nothing. My house is full of gifts.

Quoted in the title.

Yeah. I wish I believed in such things.

In my family we do magic sometimes. Tarot for clarity in decision-making. Sacrifices to local spirits when we need assistance making a change. (Spirits seem more approachable than gods.) Sometimes I call our dog the spirit of our house, because he has a brave, bullish personality that is different from any of the rest of us (but has qualities we need).

All of this is made up, of course — explicitly made up, by us. We’re children fumbling for explanations of adult things. I don’t have any particular tradition that tells me that there is a “house spirit” or a “city spirit” to pray to. We used to live in a house with trees and bushes in the front yard that attracted so many bees they HUMMED. I would go out sometimes and stand in front of the biggest tree and listen to the bees and feel… something. But I don’t have a tradition to tell me what.

(I should say — I have never once gotten the impression from any sort of modern “pagan” that they know, either. I always get the sense that they, too, are making it up as they go. I think religion, which literally means connection, can’t be separated from a cultural and physical environment. What worked a Viking village will not work for me. Or at least, it will not work the same. Though I freely admit there are still glimpses of power, as in your ring.)

It’s not real. It’s made up of little fragments of paganism and Catholicism and half-digested readings in anthropology and probably Star Trek and Clan of the Cave Bear, too. Still… it’s not a bad thing to do. There’s something about treating the world as though it’s alive, full of little bits of spirit and power that I am in relationship with, that puts me deeply at peace. That makes me feel respect and humility and connection, instead of anxiety and alienation and a desire to control.

It is all made up, on the fly, with no deep background to support it. I wish it were otherwise.

This was such a beautiful, thought-provoking, and compassionate essay, Sarah. I was particularly struck by the idea that it is quite audacious of us to think a god would stoop to muddle around in our petty affairs. And yet we think that way all the time. (In my version, which comes straight from yoga classes, it’s sending good wishes into the universe, but same-same.)

I can be superstitious, and I have found that I’m most superstitious when I have the least power. On the day my son was waiting to hear whether he had gotten into his top-choice university, I went to the school library and organized all the Diary of a Wimpy Kid, Warriors, and Rick Riordan books. This was a big job! Those shelves are always a disaster. But I thought maybe if I took on this useful but thankless task, then karma would reward my son with an offer of admission. And when my daughter was waiting to hear whether she got early admission to her top-choice college, I visited the hippotherapy center next to her school on my way to pick her up, to see if my favorite pony, whom I call Emo Pony because of his dejected appearance, was there. Emo Pony is my good-luck charm. He wasn’t in the corral, but then as I turned into the school parking lot he and his rider crossed in front of my car. Whoo hoo! Luck! I thought.

Did these stratagems “work”? Yes and no. Yes, because my kids both did find out shortly after my superstitious activity that they did indeed get into their top choices. But of course no, because superstition is pretend, and organizing those shelves and looking at Emo Pony have no bearing on admissions decisions, obviously. At least those library shelves were organized for a couple of days before they reverted to their usual chaos.

Magic, tarot, witchcraft, and--let’s go ahead and be controversial--religion all give us a sense of control when we feel powerless. It is fascinating to me how intractable that human need is, and how many forms we’ve developed for meeting that need.